For the past several years, NSRWA has been collaborating with teachers and students from Scituate to High School to study our local salt marshes. Salt marshes make for a fantastic and unique outdoor classroom. The convergence of tides, vegetation, fauna, and human history create a dynamic landscape where endless scientific concepts can be studied.

This fall, Mr. Perrotto’s Environmental Science class has been studying the global issue of “clean, safe water.” As part of that, they are looking specifically at coastal and marine issues and how the watershed is involved in the health of the ocean. In late September, the class joined NSRWA’s Watershed Ecologist out on a salt marsh in Scituate to see some of these concepts first-hand.

The class showed up at the field site ready to go! They came prepared with field notebooks, plant identification guides, and tools for measuring features and conditions of the marsh. We started out with a safety talk and then jumped into documenting the basic site conditions such as time of day, temperature, weather, tide, recent rainfall, and other observations that could influence our findings. We then set out onto the marsh. Previously, in class, we had used well-established methods to assign the number and location of marsh transects that we would study. With the coordinates of those locations in hand, the students used a handheld GPS and compasses to find their way to the starting point.

After finding the start point we laid out 300 meter long measuring tapes to establish our transects. Along this transect we conducted two types of measurements: 1) Quadrat surveys allowed us to estimate the percent cover of vegetation on the marsh and the various plant species present. 2) Belt surveys measure the width (distance) that different vegetation types make up across the marsh. The vegetation types, and species present, help determine the function and health of various parts of the marsh. The quadrat and belt surveys were conducted along the full width of the marsh, from the upland wooded edge to the river.

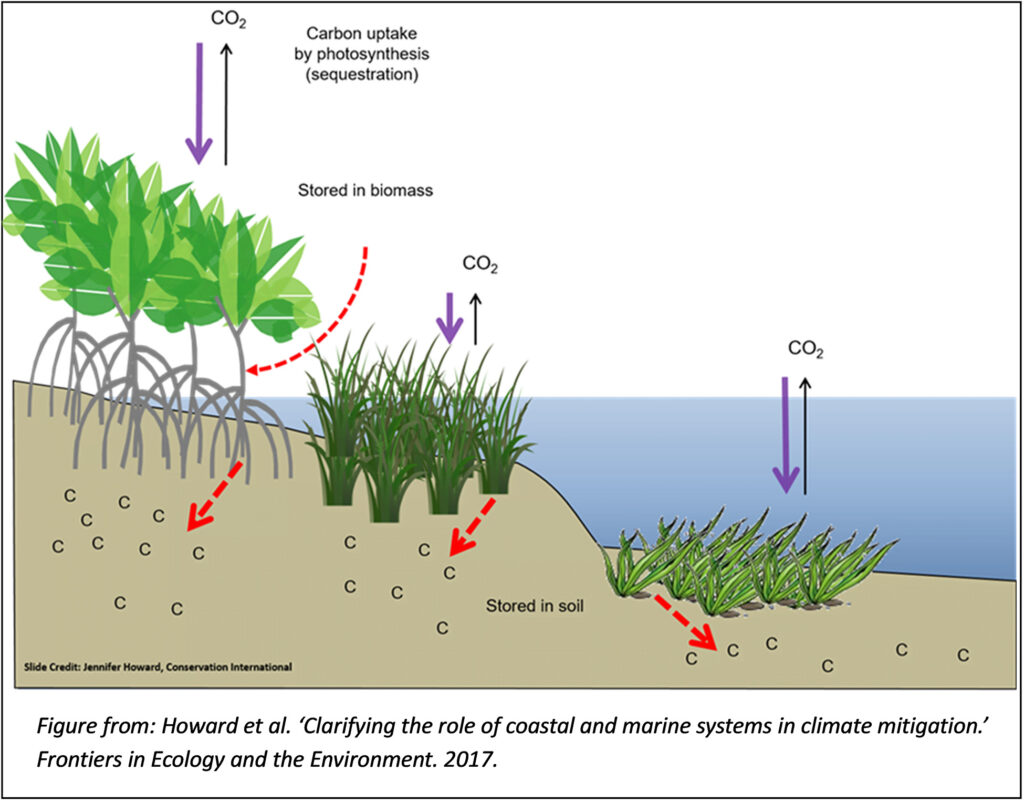

The students have also recently been studying “blue carbon”. Blue carbon is the term for carbon that is captured by the world’s ocean and coastal ecosystems. It refers to carbon that is stored by plants, algae, and phytoplankton in coastal and marine ecosystems, such as mangrove forests, seagrass beds, and salt marshes. Most of the carbon taken up by these ecosystems is stored below ground where we can’t see it, but it is still there. In the classroom, the students are learning about a computer model that can help coastal managers determine how much carbon a salt marsh will store in a season. This model was developed by the ‘Bringing Wetlands to Market (BWM)’ project which is a collaborative research project led by Waquoit Bay National Estuarine Research Reserve in Falmouth.

In our local marsh the students set out to collect field measurements that they could plug into the BWM model. The primary data needed for the model was:

1) Photosynthetically active radiation (PAR) which defines the amount of sunlight available to plants for photosynthesis. More light = faster plant growth = more carbon storage.

2) Soil temperature: As temperature increases, the marsh soil tends to give off more carbon dioxide and store less carbon due to a higher rate of metabolism by bacteria which increases decomposition.

3) Soil porewater salinity: This is the amount of salt within the marsh soils rather than in the surface waters of the river or on the marsh. Porewater salinity is dictated by the frequency and duration of coverage of a marsh by salty tides. Marshes that are inundated by salty tides tend to release less carbon dioxide and methane than drier soils or soils with fresher water.

The students broke into groups to collect all of these parameters and enter the data into their field logbooks. Back at the classroom they will be able to input these measurements into the model and learn about local salt marshes capacity for carbon sequestration.

The students broke into groups to collect all of these parameters and enter the data into their field logbooks. Back at the classroom they will be able to input these measurements into the model and learn about local salt marshes capacity for carbon sequestration.

In addition to these well-defined scientific approaches, we also took some time for general observations. We spotted shore birds along the tide line, fiddler crabs in the creek banks, and small fish in the pools on the marsh. We also took note of the human surroundings including stormwater outfalls discharging to the marsh, salt marsh ditches, remnant debris, dog walkers, and boaters. All of these informal observations can be ideas for new hypotheses and clues about existing conditions.

We are looking forward to many more years of collaboration with Scituate High School!