Raising the Bar

The following is the fifth installment of a twelve-part series on the history of the organization. You can read the other installments here.

By Jim Glinski, Scituate

The NSRWA continued to evolve and grow as an organization. As Executive Director Samantha Woods stated at the time of the NSRWA’s 40th anniversary in 2010, by 1990 the Association was “raising the bar for the rivers and making an organization that could be sustained over time to not only protect it when immediate threats happened but to proactively restore water quality and raise awareness about the watershed and its rivers for the long term.”

As was noted earlier, by this time the Association had a full-time director and would soon have a new permanent headquarters in Norwell. In August 1989, the NSWRA announced a pledge of $250,000 from a local family, who were concerned about the degradation of the water quality of the North River and wanted to see some steps taken to preserve and improve the river. The NSRWA would use some of this pledge to replace lost state funding, which had been stopped, for pollution source location testing. Only $15,000 of this pledge was given directly to the NSRWA and was contingent on the Association matching the $15,000. This money would be used to create a full-time staff position and the organization’s first Executive Director, Dan Jones, was hired. The pledge also allowed the NSRWA to initiate many other programs which helped to improve the watershed’s environment.

In July 1988, Dan Jones who was a volunteer at that time, organized the first annual NSRWA River Clean-Up Day. Around 200 volunteers were rewarded with an official NSRWA T-shirt for gathering up trash in and along the North and South Rivers, which included bottles, cans, refrigerators and motorcycles. This increasingly popular event continued for many years and generated a lot of favorable publicity for the NSRWA, as local newspapers published pictures of smiling volunteers hauling away the debris they had collected in and along the rivers.

In July 1988, Dan Jones who was a volunteer at that time, organized the first annual NSRWA River Clean-Up Day. Around 200 volunteers were rewarded with an official NSRWA T-shirt for gathering up trash in and along the North and South Rivers, which included bottles, cans, refrigerators and motorcycles. This increasingly popular event continued for many years and generated a lot of favorable publicity for the NSRWA, as local newspapers published pictures of smiling volunteers hauling away the debris they had collected in and along the rivers.

In 1989, the Air Force was asked to meet with the North River Commission (NRC) concerning several Protective Order violations which resulted from its plans to rebuild and expand their cottages on Fourth Cliff and their claim that NRC regulations did not apply to them. The NRC’s major concerns were the faulty septic system on the site and the depositing of illegal fill on a barrier beach. At a March 4 meeting with the NRC and other concerned parties, the Air Force committed to install a new septic system, remove the rubble from the top and northern face of the coastal bank and beach area, and review other on-site measures with the North River Commission; a good example of what active citizen engagement could accomplish.

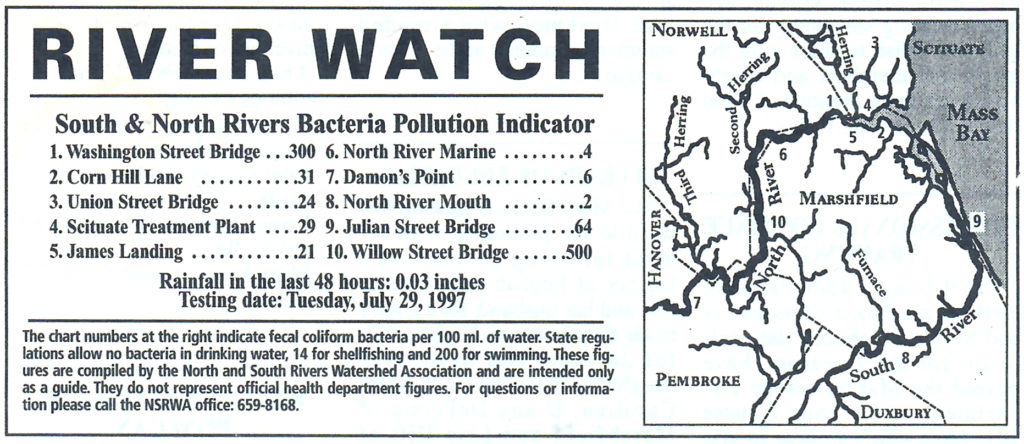

In 1990, the NSRWA began its RiverWatch program. Evolving out of the state’s Adopt- a -Stream program, RiverWatch created a focus for the many people who wanted to help the rivers, with 75 people attending the first meeting at the Norwell Library. The program trained citizen scientists to collect data on the condition of the watershed’s water and was the beginning of NSRWA’s citizen-led water quality monitoring program. These volunteer citizen scientists would be crucial to the success of the Watershed’s federally funded study to pinpoint pollution sources on the North River. The study would focus on five areas: Third Herring Brook, between Hanover and Norwell; Dwelley’s Creek in Norwell; and the stretches of the river between Norwell’s Bridge Street and Marshfield’s Union Street, near King’s Landing in Norwell and near Marshfield’s Riverside Circle. As a result of the study Riverside Circle was found to have serious concerns, including an illegally installed pipe emptying into the marsh at the bottom of the circle and several homes with failing septic systems. This source of pollution was eliminated when, in the spring of 1995 with funding from the MassBays program, the Marshfield DPW completed a sophisticated filtration/drainage system on Riverside Circle, which would prevent bacteria and other pollutants from entering the river.

1990 also saw the advent of the increasingly popular Great River Race. This 7 mile race, begins at the Bridge Street canoe launch in Norwell and ends at Indian Head River take out in Hanover. The race includes separate categories for individual and duo/group canoes, kayaks, sailboats, rowing dories and homemade rafts. Although the race does reward participants for their paddling or rowing skills, it is really about spending a summer day on the North River, enjoying the spectacular views the river offers and joining others to celebrate the ecologically diverse and historically rich waterway.

1990 also saw the advent of the increasingly popular Great River Race. This 7 mile race, begins at the Bridge Street canoe launch in Norwell and ends at Indian Head River take out in Hanover. The race includes separate categories for individual and duo/group canoes, kayaks, sailboats, rowing dories and homemade rafts. Although the race does reward participants for their paddling or rowing skills, it is really about spending a summer day on the North River, enjoying the spectacular views the river offers and joining others to celebrate the ecologically diverse and historically rich waterway.

In the spring of 1991, the NSRWA published its first Guide to the North and South Rivers, the first comprehensive map of the two historic and complex rivers. The guide was the product of over a year of effort by Cap Vinal and Dan Jones, who along with many others, created a convenient guide to river history, geography and culture, and an easy to use tide key. A free copy of the guide was sent to all current members and additional copies were available for purchase. In 2019, the NSRWA published the 5th edition of the guide.

In the spring of 1991, the NSRWA published its first Guide to the North and South Rivers, the first comprehensive map of the two historic and complex rivers. The guide was the product of over a year of effort by Cap Vinal and Dan Jones, who along with many others, created a convenient guide to river history, geography and culture, and an easy to use tide key. A free copy of the guide was sent to all current members and additional copies were available for purchase. In 2019, the NSRWA published the 5th edition of the guide.

When the Association dropped its lawsuit against the Town of Scituate in April 1992 over the contamination of the North River by its sewage plant, it decided to turn its attention to other ways to clean the river’s water and launched Harvest 95. This was a program, which received nearly $70,000 in funding, half from an EPA grant, to reduce pollution from storm drains and other sources in the hope of reopening the North and South River shellfish beds, which were a barometer of how healthy and clean the rIvers were.

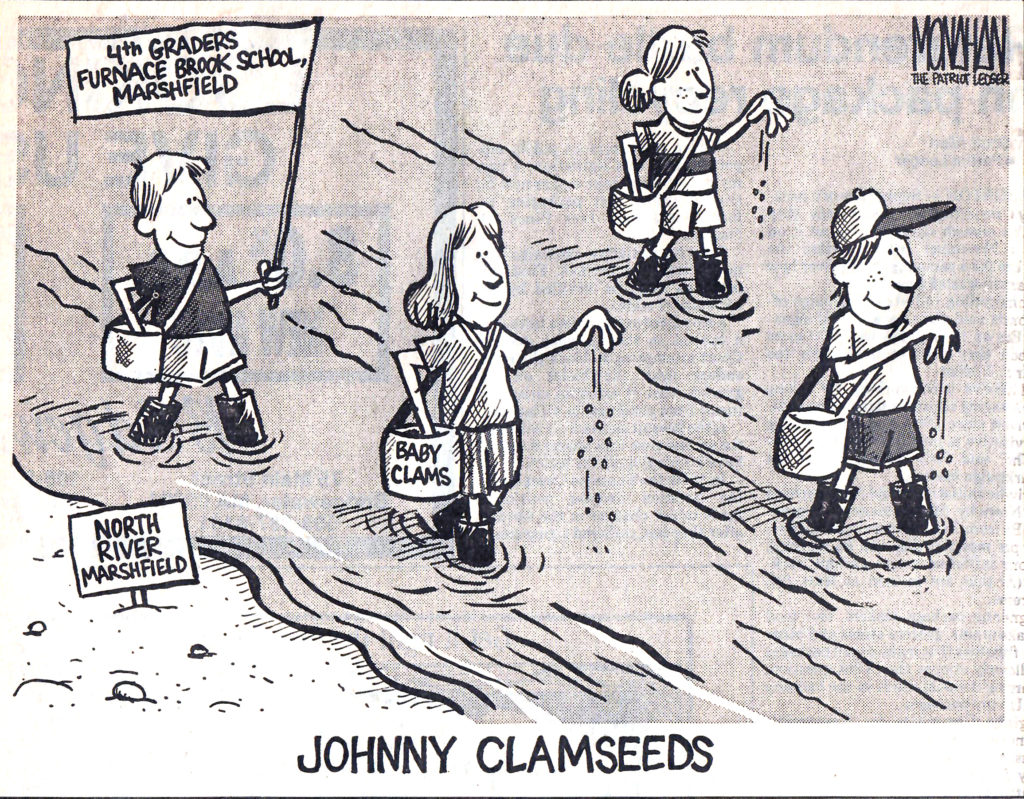

A unique aspect of Harvest 95 was getting local students involved in seeding clam beds. In June 1992, 21 fourth-graders in Joyce Sullivan’s class from Marshfield’s Furnace Brook School assisted by volunteers from NSRWA and assistant professor of marine biology Brian Beal, who designed the project, planted 15,000 baby clams in mudflats near the Route 3A bridge and on flats in the South River in the Humarock section of Scituate. As NSRWA president Carolyn Sones noted, “the association hopes the children will learn the importance of preserving the water quality” since they were the next generation of caretakers of the rivers. Unfortunately, as professor Beal had predicted, the pin-head sized seedlings did not survive the summer. Undaunted by this failure, the school children in Joyce Sullivan’s class and NSRWA volunteers planted new clams at the same sites which were many times larger and yielded better results. In April, fourth-graders from the Montessori Community School in Scituate planted 6,000 baby clams in the North River. These would be the first of many educational programs launched by the NSRWA.

A unique aspect of Harvest 95 was getting local students involved in seeding clam beds. In June 1992, 21 fourth-graders in Joyce Sullivan’s class from Marshfield’s Furnace Brook School assisted by volunteers from NSRWA and assistant professor of marine biology Brian Beal, who designed the project, planted 15,000 baby clams in mudflats near the Route 3A bridge and on flats in the South River in the Humarock section of Scituate. As NSRWA president Carolyn Sones noted, “the association hopes the children will learn the importance of preserving the water quality” since they were the next generation of caretakers of the rivers. Unfortunately, as professor Beal had predicted, the pin-head sized seedlings did not survive the summer. Undaunted by this failure, the school children in Joyce Sullivan’s class and NSRWA volunteers planted new clams at the same sites which were many times larger and yielded better results. In April, fourth-graders from the Montessori Community School in Scituate planted 6,000 baby clams in the North River. These would be the first of many educational programs launched by the NSRWA.

Meanwhile, the NSRWA continued its efforts to identify and reduce the stormwater pollution that was impacting the shellfish beds. Although it did not reach its goal of opening the shellfish beds by 1995, in April 1996, 194 acres of shellfish beds along the North River from Damon’s Point to the mouth were opened for a month. They would be closed from May to November, but reopened in December, marking the success of the Harvest 95 project.

In the spring of 1993, the Watershed received a $3,000 Greenways Small Grant from the state Department of Environmental Management (DEM) and took the lead on the Indian Head River Greenway Program, with NSRWA Board of Director’s member, J.E. Ingoldsby taking on the role of planning and coordinating the project. The project was a campaign to protect the Indian Head River and its fish habitat, while at the same time making the area accessible to more people. Its specific goals included improving the parking lot and canoe launch near the West Elm Street bridge which marked the border of Hanover and Pembroke, building a picnic area and 10-mile trail system with signs and historical markers along the site of the abandoned rail bed running from Hanover Four Corners to the Rockland line, and improving the fish ladders along the Indian Head River, which had the second-largest shad run in the state. To help achieve this last goal, in fall of 1995, supported with grants from DEM and the state Riverways Program, the NSRWA recruited students from the South Shore Vocational High School to repair fish ladders at Luddam’s Ford on the Hanover/Pembroke line.

In the spring of 1995, the NSRWA was awarded $60,000 in grant funds to provide public outreach for the Superfund Cleanup of hazardous waste at the South Weymouth Naval Air Station, which covered 1,442 acres in the towns of Abington, Rockland, and Weymouth. The NSRWA decided to get involved in this project because French Stream, which flows south from the base, links the Air Station to the North River watershed. Involvement in this project would also provide an opportunity to spread awareness of the NSRWA and its efforts to protect the waters of the North and South Rivers watershed to citizens of towns where it has not previously had a large presence.

In the spring of 1995, the NSRWA was awarded $60,000 in grant funds to provide public outreach for the Superfund Cleanup of hazardous waste at the South Weymouth Naval Air Station, which covered 1,442 acres in the towns of Abington, Rockland, and Weymouth. The NSRWA decided to get involved in this project because French Stream, which flows south from the base, links the Air Station to the North River watershed. Involvement in this project would also provide an opportunity to spread awareness of the NSRWA and its efforts to protect the waters of the North and South Rivers watershed to citizens of towns where it has not previously had a large presence.

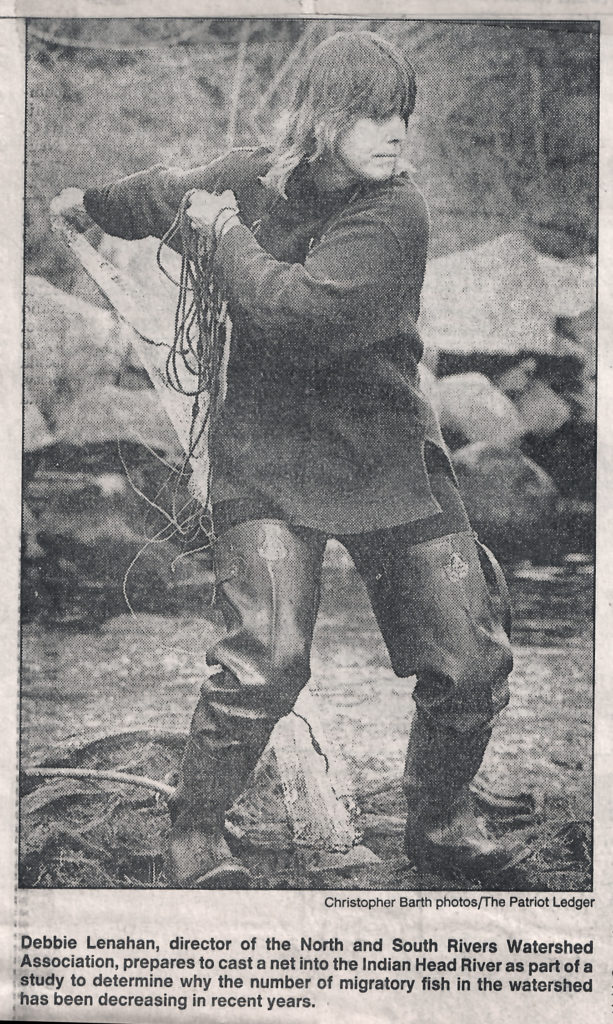

With the success of Harvest 95, the new drainage system at Riverside Circle installed, and the RiverWatch water monitoring programs running smoothly, in April 1996, the 2nd executive director of the NSRWA Debbie Lenahan, announced she was stepping down.

Debbie, who had earlier been an active volunteer member of NSRWA in the office and in the RiverWatch program, became executive director in July 1994, after serving in the part-time position of Director of Development. She would return to NSRWA to serve as its president in the early 2000s. A Boston Globe article on her departure provided a good snapshot of the NSRWA in 1996, as an organization with 800 members, a $75,000 annual budget, 1½ employees, and 80 active volunteers.

Debbie would be succeeded by Norwell resident Steven P. Ivas. Steve had worked in the Peace Corps early in his career teaching fish farming in the African nation of Zaire and spent the last 11 years working at the Metropolitan District Commission’s reservations and historic sites division. Steve hoped that the NSRWA could take a more active role in community water quality programs and open spaces issues. He believed the NSRWA could help resolve disputes between local, state, and private groups, such as the dispute between the state and Marshfield over the town’s sewer expansion. He also wanted to create management plans town officials could use to make decisions that affected the environment in their towns. Some of the specific actions by the NSRWA during 1996 which reflected his goals were assisting Pembroke to set up an open space committee, helping to conserve the 174 acre Donovan property in Norwell, and helping the New England Forestry Foundation create a management plan for Marshfield’s Nelson Forest. In addition, Steve set the ambitious goal of growing Association membership to 2,000 members by the year 2000. Although this goal was not achieved, NSRWA membership grew to over 1,100 by the end of his tenure in 1998.

Although not formally announced until April 1997, in the fall of 1996, after RiverWatch water monitoring results indicated that the most consistently polluted waters in the watershed were areas of the South River near Marshfield’s business district’s Willow Street and Julian Street bridges, the NSRWA announced its South River Initiative project. This initiative would be a six-year education, public access, and clean up project which envisioned the creation of a group consisting of business representatives, town officials, and the general public that would steer the direction of the project so that the NSRWA could play a behind-the-scenes role in it. The initiative received an early set back when the Marshfield Board of Selectman refused to accept a grant from the state Department of Environmental Protection that would have gone toward the clean up of the South River, even though the grant was supported by the Marshfield Board of Health, Mass Bays, NSRWA, and the DEP. Marshfield’s selectmen also rejected an invitation to join the South River Initiative and grant applications totaling $81,400. However, to help jump start the project, the NSRWA received grants for the initiative totaling $24,700 from the Massachusetts Environmental Trust and the Boston Foundation to be followed, in November 1998, by a $25,000 grant from the state Executive Office of Environmental Affairs. Similar to Harvest 95, the South River Initiative would involve students in its efforts to clean up the South River. In April 1998, students in Dr. Ann Thomae’s Scituate High School 11th grade chemistry class conducted a series of experiments on the salt concentrations in the water of the South River, as part of their project to better understand where there was pollution in the river and where it was going. As Steve Ivas commented, this type of lesson “gets the kids involved in a scientific inquiry and help decision-makers make good decisions about the future of the river.”

Although not formally announced until April 1997, in the fall of 1996, after RiverWatch water monitoring results indicated that the most consistently polluted waters in the watershed were areas of the South River near Marshfield’s business district’s Willow Street and Julian Street bridges, the NSRWA announced its South River Initiative project. This initiative would be a six-year education, public access, and clean up project which envisioned the creation of a group consisting of business representatives, town officials, and the general public that would steer the direction of the project so that the NSRWA could play a behind-the-scenes role in it. The initiative received an early set back when the Marshfield Board of Selectman refused to accept a grant from the state Department of Environmental Protection that would have gone toward the clean up of the South River, even though the grant was supported by the Marshfield Board of Health, Mass Bays, NSRWA, and the DEP. Marshfield’s selectmen also rejected an invitation to join the South River Initiative and grant applications totaling $81,400. However, to help jump start the project, the NSRWA received grants for the initiative totaling $24,700 from the Massachusetts Environmental Trust and the Boston Foundation to be followed, in November 1998, by a $25,000 grant from the state Executive Office of Environmental Affairs. Similar to Harvest 95, the South River Initiative would involve students in its efforts to clean up the South River. In April 1998, students in Dr. Ann Thomae’s Scituate High School 11th grade chemistry class conducted a series of experiments on the salt concentrations in the water of the South River, as part of their project to better understand where there was pollution in the river and where it was going. As Steve Ivas commented, this type of lesson “gets the kids involved in a scientific inquiry and help decision-makers make good decisions about the future of the river.”