Effective Campaigns and Growing Partnerships

By Jim Glinski, Scituate

By Jim Glinski, Scituate

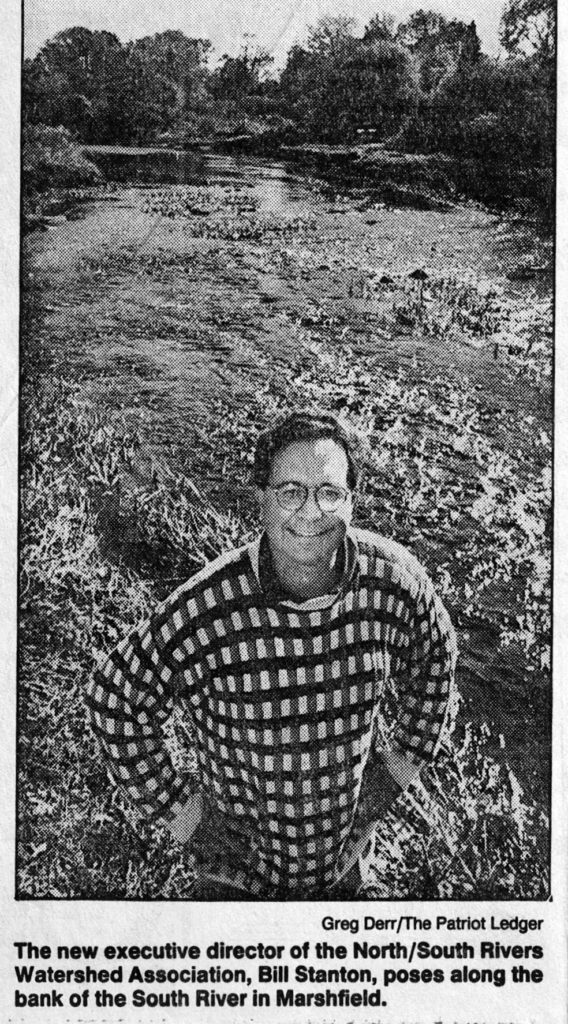

In November 1998, Steve Ivas was succeeded as executive director of the NSRWA by Bill Stanton, who was the first executive director who did not have a science-based professional background. Bill was a lawyer-environmentalist, who was chairman of the Marshfield Conservation Commission and recently spent 4 ½ years running the Massachusetts Audubon Society’s $34 million fundraising campaign to acquire more land, improve visitor centers, and establish endowments. Bill was attracted to the NSRWA in part by its South River Initiative because it matched his belief of approaching the problems of the river regionally. He believed that: “as a society we have to come up with solutions. Pointing fingers at one town doesn’t work. If you look at it regionally then you can solve it collectively.” In another example of taking a more regional approach, in 2000, the NSRWA joined forces with the Jones River Watershed Association, the Eel River Watershed, and the Taunton River Watershed Alliance creating the Watershed Action Alliance which addressed watershed issues in southeastern Massachusetts. Some of the issues Bill planned to focus on were the MBTA’s Greenbush layover station proposal, land acquisition, which he hoped would be the result of a variety of conservation groups working together, and the extension of the Marshfield sewer system to reduce pollution in the South River.

The Watershed Association first became interested in the Greenbush Old Colony Railroad Restoration Project in 1994, when plans for the project revealed that the railroad would run through the watershed area, and that a train storage and maintenance facility was planned on the south side of the Driftway in Scituate, directly abutting the marshes around First Herring Brook. Although it did not take a position on whether or not the Greenbush line should be restored, having spent five years attempting to locate and eliminate sources of pollution in the watershed, the NSRWA encouraged changing the planned location for the layover facility to a less environmentally fragile location, such as the soon to be capped Scituate landfill site.

The Watershed Association first became interested in the Greenbush Old Colony Railroad Restoration Project in 1994, when plans for the project revealed that the railroad would run through the watershed area, and that a train storage and maintenance facility was planned on the south side of the Driftway in Scituate, directly abutting the marshes around First Herring Brook. Although it did not take a position on whether or not the Greenbush line should be restored, having spent five years attempting to locate and eliminate sources of pollution in the watershed, the NSRWA encouraged changing the planned location for the layover facility to a less environmentally fragile location, such as the soon to be capped Scituate landfill site.

In addition, the bright lights, diesel trains, and maintenance facility so close to the river and marsh would significantly detract from the scenic character of the river. As the project proceeded into the new century, plans still proposed a layover site on the south side of the Driftway, which led the NSRWA to launch its “Save Our River” campaign in support of a site north of the Driftway. Similar to the campaign against the Scituate Sewage Treatment Plant, the NSRWA created bumper stickers, which this time read “Save Our River.”

Watershed executive director, Bill Stanton, was able to bring together a broad coalition, which included train proponents, train opponents, local officials, and state officials, who all believed that any layover facility should not be built next to the North River. The result was that in issuing its final environmental impact report on the rail restoration project on August 20, 2001, the state Executive Office of Environmental Affairs announced that it would not certify the project unless the layover facility in Scituate was placed north of the Driftway. On the announcement of this decision Secretary of Environmental Affairs, Robert Durand, noted that “by far the largest volume of comments received on the FEIR (Final Environmental Impact Report) concern the siting of the layover facility, within the Greenbush area of Scituate.” Hundreds of letters and e-mails were sent to the Secretary, which did not exaggerate the facts but focused on the simple fact that there was a viable alternative to the proposal of the MBTA that would have scarred the North River forever.

In a November 1999 Marshfield Mariner article, Stanton highlighted the benefits of the Watershed Association’s River Watch program. By sampling the same 10 sites through the last six summers, the program established consistent results that identified areas of concern and led to positive impacts on local towns. In Scituate, the Town used a $60,000 state grant from the Department of Coastal Management to clean up storm water runoff in the Herring River that feeds into the mouth of the North River. The Town also continued to make significant improvements to its sewage treatment plant. After years of battling each other the Watershed Association and the Town of Scituate had come together to work on practical solutions that would benefit the citizens of Scituate and improve the water quality of the North River.

Between 1971 and 1999 over 11,000 acres of land within the North and South Rivers watershed had been developed. This is an area equivalent to the size of the Town of Scituate. The NSRWA had always been a big proponent of protecting open space. Although the Watershed Association did not own conservation land, it promoted projects which encouraged open space preservation because lands that are protected don’t pollute the rivers, provide valuable habitat for wildlife, and provide valuable places for recreation. In 1999, the Watershed received a boost in its efforts to protect lands along the rivers when it received a $5,000 grant from the state for its North River Mapping project. This project would be a cooperative effort with the Mass Audubon Society, the Trustees of Reservations, and the Wildlands Trust of Southeastern Massachusetts, to map the entire North River to identify habitats that were crucial for open space and needed protection. Watershed towns and conservation organizations would then be able to use the map as a tool to prioritize parcels for acquisition or conservation restrictions.

In September 2000, efforts to preserve open space received a huge boost with the passage of the Massachusetts Community Preservation Act (CPA). This act “enabled adopting communities to raise funds to create local dedicated funds for open space preservation, restoration of historic resources, development of affordable housing, and the acquisition and development of outdoor recreational facilities.” Funding for these purposes would come from a surcharge on the property tax in adopting towns not to exceed 3 % of the tax and must be approved by voters in the town. A state fund with money from surcharges on fees for recording deeds and other property transactions would provide matching grants to towns that joined the program.

NSRWA executive director Bill Stanton, realizing that the act provided an opportunity for towns who adopted the act early to receive significant funding from the state (a bigger piece of a $26 million pie in 2001), encouraged towns in the watershed to adopt the program as soon as possible and vigorously encouraged the adoption of CPA by voters at town meetings. This was one of the major reasons Bill was selected as Marshfield’s 2001 Citizen of the Year. By 2002, the towns of Duxbury, Marshfield, Cohasset, Scituate, and Norwell had approved adopting CPA. Marshfield would use CPA funds to develop an open spaces plan and to acquire parcels of land on both the North and South Rivers and to later fund the development of the South River Greenway Park.

NSRWA executive director Bill Stanton, realizing that the act provided an opportunity for towns who adopted the act early to receive significant funding from the state (a bigger piece of a $26 million pie in 2001), encouraged towns in the watershed to adopt the program as soon as possible and vigorously encouraged the adoption of CPA by voters at town meetings. This was one of the major reasons Bill was selected as Marshfield’s 2001 Citizen of the Year. By 2002, the towns of Duxbury, Marshfield, Cohasset, Scituate, and Norwell had approved adopting CPA. Marshfield would use CPA funds to develop an open spaces plan and to acquire parcels of land on both the North and South Rivers and to later fund the development of the South River Greenway Park.

As a result of NSRWA programs such as its River Watch water quality testing program, Harvest 95, and the South River Initiative, it was clear that one of the major sources of pollution in the North and South Rivers was runoff from septic systems in areas in Marshfield near the rivers, including the Marshfield High School complex and the South River School. In 1994, the state issued an Administrative Order to the Town to repair the faulty septic systems. This pollution had closed shellfish beds, degraded the spawning grounds for the region’s fish, and threatened to decrease recreational uses of the river. There were a few plans offered by the Marshfield DPW to solve the septic issues, with the NSRWA and the state Department of Environmental Protection voicing support for an extension of the town’s sewer system along Route 139, which would connect all municipal buildings, businesses, and residences along Route 139 to town sewage. Unfortunately, voters rejected this proposal at a special town meeting in March 1994, threatening further damage to the water quality of the South River and continuing legal action by the state Attorney General’s office. After several years of extending sewer to specific neighborhoods, but rejecting the larger project of extending sewer to the town center, in the spring of 2000, Marshfield voters finally approved the extension of its sewer line to the town center.

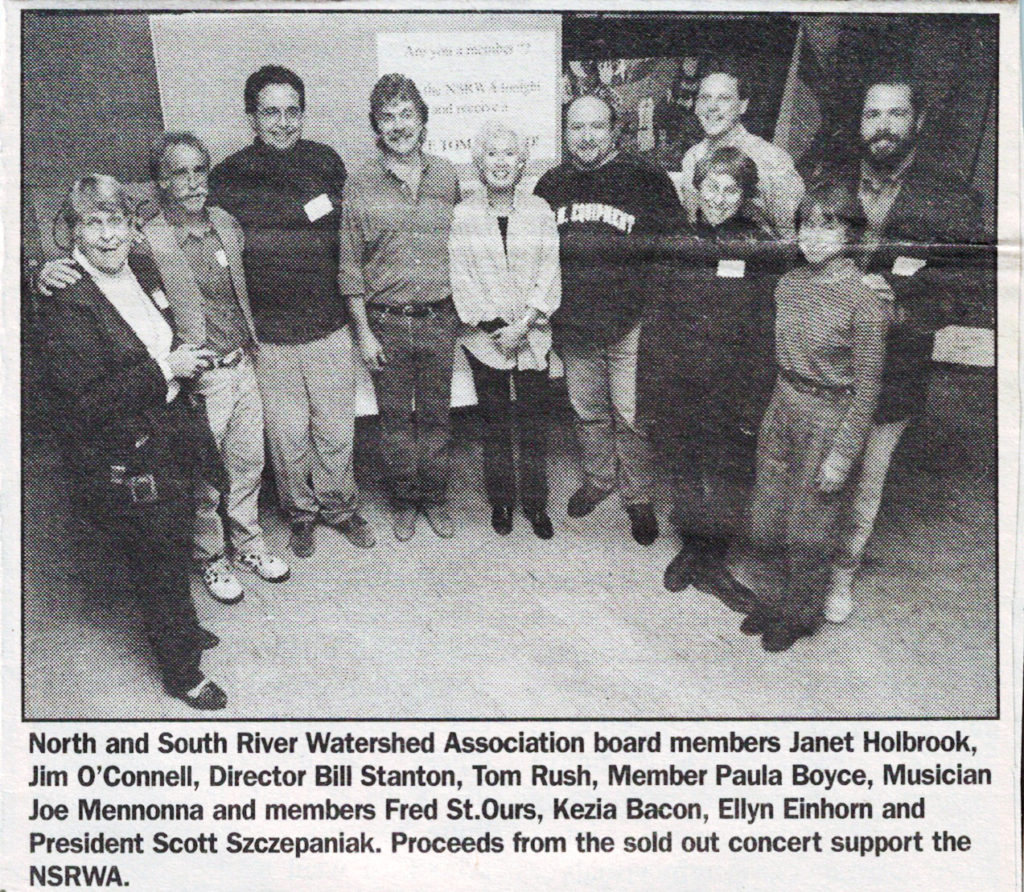

During Stanton’s tenure, the Watershed Association continued to hold many recreational and fundraising events, which generated a large amount of positive publicity for the organization. The Great River Race and River Clean Up Day continued, with increased public participation in both of these annual events. Additional Association sponsored events included a moonlight paddle, a house tour, kayak workshops, the Melonseed River Race, and the return of the popular Yoga at the River’s Edge. Well known musicians also contributed their support to the Watershed Association. Folk music legend Tom Rush performed benefit concerts in October 1997 and 1998. Members of the famous rock band Aerosmith attended a benefit for the NSRWA at the Mount Blue restaurant in Norwell, of which they were part owners, with the proceeds used to support the NSRWA’s educational programs and workshops.

In the summer of 2001, the NSRWA teamed up with Massachusetts Audubon to offer a week-long River Adventurers Camp. Sixteen campers ages 13-15, under the guidance of Doug Lowry, learned basic canoe and kayak skills, along with the history, geology and nature of the rivers. The week culminated with a several day camping trip down the river. The camp would receive support from gifts given to NSRWA in honor of the memory of John Hilton, Jr, which paid for 2 of the 16 children at the camp and from Amanda Reed, a junior at Colgate University and daughter of Board member Damon Reed, who raised $6,500 for the camp by walking 270 miles on Vermont’s Long Trail.

In the summer of 2001, the NSRWA teamed up with Massachusetts Audubon to offer a week-long River Adventurers Camp. Sixteen campers ages 13-15, under the guidance of Doug Lowry, learned basic canoe and kayak skills, along with the history, geology and nature of the rivers. The week culminated with a several day camping trip down the river. The camp would receive support from gifts given to NSRWA in honor of the memory of John Hilton, Jr, which paid for 2 of the 16 children at the camp and from Amanda Reed, a junior at Colgate University and daughter of Board member Damon Reed, who raised $6,500 for the camp by walking 270 miles on Vermont’s Long Trail.

One development that would pay dividends for the NSRWA for years to come was its partnership with the Mass Bays Program. As a result of a $45,000 grant from the Massachusetts Bay National Estuary Program (MBP) in 2001 and matching funding from the NSRWA, the NSRWA hired Alison Demong as a new full-time director of Community Programs. The MBP was launched in 1988 with settlement money from the lawsuit against the Commonwealth of Massachusetts for the pollution of Boston Harbor. The MBP region covers 800 miles of coastline from the tip of Cape Cod to the New Hampshire border. To cover such a large area the MBP placed staff in nonprofit organizations, such as the NSRWA, which became the MBP’s new partner on the South Shore in 2001. In her role as a representative of Mass Bays, Alison’s job would be to work closely with municipalities on the South Shore to find solutions to environmental concerns that were important to all of the South Shore coastal communities. Because the Mass Bays South Shore geographic area was broader than that of the NSRWA, she would be focusing her efforts on not only the North and South Rivers watershed, but also towns outside it, including Cohasset, Kingston, and Plymouth. Another benefit of this new partnership was its ability to obtain more money (over $700,000 in the first year and a half of the partnership) for environmental projects for the South Shore. Clearly, partnering with the Mass Bays Program directly complimented the work of the NSRWA and strengthened its presence as a regional environmental organization on the South Shore.

One development that would pay dividends for the NSRWA for years to come was its partnership with the Mass Bays Program. As a result of a $45,000 grant from the Massachusetts Bay National Estuary Program (MBP) in 2001 and matching funding from the NSRWA, the NSRWA hired Alison Demong as a new full-time director of Community Programs. The MBP was launched in 1988 with settlement money from the lawsuit against the Commonwealth of Massachusetts for the pollution of Boston Harbor. The MBP region covers 800 miles of coastline from the tip of Cape Cod to the New Hampshire border. To cover such a large area the MBP placed staff in nonprofit organizations, such as the NSRWA, which became the MBP’s new partner on the South Shore in 2001. In her role as a representative of Mass Bays, Alison’s job would be to work closely with municipalities on the South Shore to find solutions to environmental concerns that were important to all of the South Shore coastal communities. Because the Mass Bays South Shore geographic area was broader than that of the NSRWA, she would be focusing her efforts on not only the North and South Rivers watershed, but also towns outside it, including Cohasset, Kingston, and Plymouth. Another benefit of this new partnership was its ability to obtain more money (over $700,000 in the first year and a half of the partnership) for environmental projects for the South Shore. Clearly, partnering with the Mass Bays Program directly complimented the work of the NSRWA and strengthened its presence as a regional environmental organization on the South Shore.

In 2000, the NSRWA formed another important partnership with the First Herring Brook Watershed Initiative (FHBWI) in Scituate. In contrast to the broad scope of the Mass Bays Programs, the FHBWI concentrated on the sub-watershed of the First Herring Brook, a tributary of the North River. The FHBWI’s affiliation with the NSRWA enabled it to share resources and the nonprofit status of the NSRWA. The NSRWA assisted the FHBWI in applying for grants, including the initial grant from the Department of Environmental Protection to fund the First Herring Brook Source Water Protection Project. It also helped the FHBWI get support for the project from the Town of Scituate. One example of this was NSRWA’s executive director Bill Stanton’s heartfelt speech in support of a town article to fund the purchase of land abutting Tack Factory Pond, part of Scituate’s drinking water supply, which contributed to its successful passage. The FHBWI’s primary purpose was to identify the full extent of water supply tributaries, associated wetland resource areas, and water bodies within the First Herring Brook Watershed. By 2003, the project led to a new, accurate map of the watershed and the development of a surface water supply protection plan for the Town of Scituate. The FHBWI also served as a role model for how local citizens could get involved in environmental issues facing their communities.

In 2000, the NSRWA formed another important partnership with the First Herring Brook Watershed Initiative (FHBWI) in Scituate. In contrast to the broad scope of the Mass Bays Programs, the FHBWI concentrated on the sub-watershed of the First Herring Brook, a tributary of the North River. The FHBWI’s affiliation with the NSRWA enabled it to share resources and the nonprofit status of the NSRWA. The NSRWA assisted the FHBWI in applying for grants, including the initial grant from the Department of Environmental Protection to fund the First Herring Brook Source Water Protection Project. It also helped the FHBWI get support for the project from the Town of Scituate. One example of this was NSRWA’s executive director Bill Stanton’s heartfelt speech in support of a town article to fund the purchase of land abutting Tack Factory Pond, part of Scituate’s drinking water supply, which contributed to its successful passage. The FHBWI’s primary purpose was to identify the full extent of water supply tributaries, associated wetland resource areas, and water bodies within the First Herring Brook Watershed. By 2003, the project led to a new, accurate map of the watershed and the development of a surface water supply protection plan for the Town of Scituate. The FHBWI also served as a role model for how local citizens could get involved in environmental issues facing their communities.

In August 2002, Samantha Woods took the helm of the NSRWA when Bill Stanton stepped down to serve as communications director for Democrat Ted LeClair’s campaign for State Senator. At the same time the Watershed hired Wendy Garpow as its new Director of Community Programs, replacing Alison Demong, who moved to France. Samantha and Wendy were previously colleagues at Horsley and Witten, an environmental engineering firm on Cape Cod. Reflecting the increased scope and activities of the NSRWA, Samantha identified a number of initiatives she planned to work on as the new executive director which included; repairing fish ladders and dams, stormwater assessment projects, new ways to implement fundraisers, a watershed-friendly landscaping program, expanding water quality monitoring, and enlarging the Watershed’s River Camp. Comparing her former job with her new one, Samantha commented that she liked the concept of being able to see her projects through to completion, instead of handing off projects she started to someone else as she had done at her previous job. As the longest-serving NSRWA executive director, still at the helm in 2020, she would get the opportunity to see several of her projects through to the end.

In August 2002, Samantha Woods took the helm of the NSRWA when Bill Stanton stepped down to serve as communications director for Democrat Ted LeClair’s campaign for State Senator. At the same time the Watershed hired Wendy Garpow as its new Director of Community Programs, replacing Alison Demong, who moved to France. Samantha and Wendy were previously colleagues at Horsley and Witten, an environmental engineering firm on Cape Cod. Reflecting the increased scope and activities of the NSRWA, Samantha identified a number of initiatives she planned to work on as the new executive director which included; repairing fish ladders and dams, stormwater assessment projects, new ways to implement fundraisers, a watershed-friendly landscaping program, expanding water quality monitoring, and enlarging the Watershed’s River Camp. Comparing her former job with her new one, Samantha commented that she liked the concept of being able to see her projects through to completion, instead of handing off projects she started to someone else as she had done at her previous job. As the longest-serving NSRWA executive director, still at the helm in 2020, she would get the opportunity to see several of her projects through to the end.