“Formerly, it is said, salmon were taken in this river.” Samuel Deane writing about the fisheries of the North River, “History of Scituate, Mass.”, published in 1831

By Warren Winders, Sea Run Brook Trout Coalition

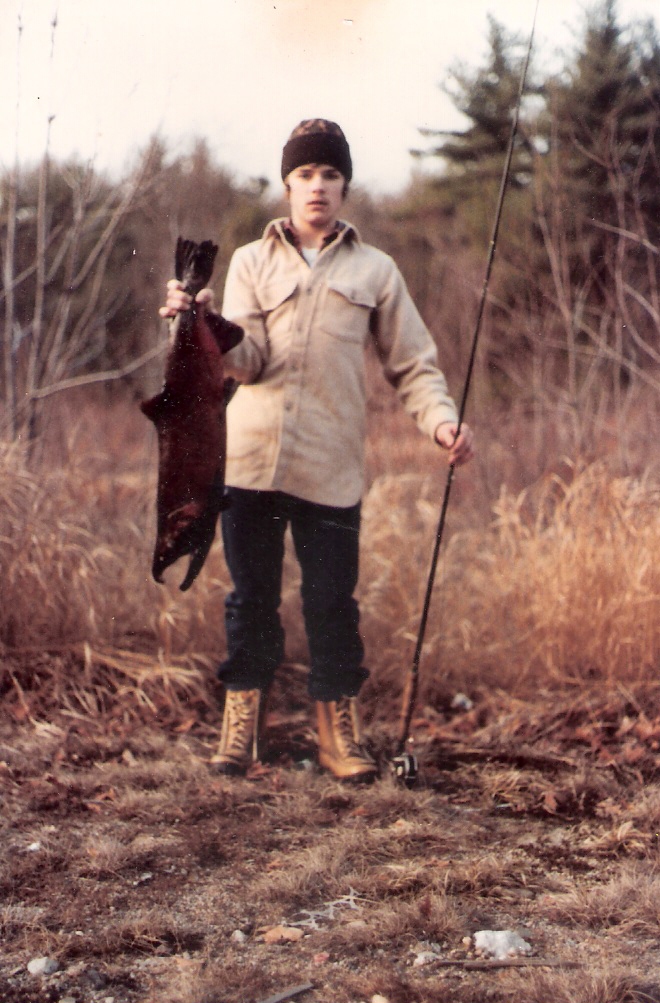

Many of us, who are of a certain age, will recall that there once was a salmon fishery on the North River, but many are not clear what happened to it or why it began in the first place. In 1969, inspired by the success of the introduction of Pacific salmon to the Great Lakes, the Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries decided to introduce the Pacific coho salmon (Oncorhynchus kisutch) to the Indian Head River, a major tributary of the North River. Our native Atlantic Salmon (Salmo salar) had long been locally extinct from the dams and pollution of our rivers from the colonial period onward. I didn’t become aware of the fishery until 1978. It had taken almost a decade of experimentation for the fall runs of cohos to build to numbers that made the fishery appealing to a large number of anglers. By the early 1980s the Indian Head River would fill with a large, fall run, of hook jawed salmon making their way upstream to the dam upstream of West Elm Street on the Hanover/Pembroke town line or Luddam’s Ford Park dam. The dam, sitting just a few hundred yards above head of tide, proved to be a convenient location for Marine Fisheries personnel to capture the ripe cohos and strip them of their milt and eggs. To ensure that there would be enough ripe salmon to strip, fishing immediately below the dam was banned and the fish ladder was blocked.

During the 1970s and 80s, both Massachusetts and New Hampshire were applying the Great Lakes, hatchery based model, described above. The fishery became so popular that there was even a group named Salmon Unlimited devoted to promoting coho salmon fishing. In the case of the North River fishery, either the Atlantic ecosystem was not receptive, or the hatchery stock being used was defective, because the fishery eventually failed. Many, myself included, blame the recovery of the striped bass population following the enactment of range-wide conservation measures. Whatever the cause, the coho program ended in the mid- to late-eighties when the salmon failed to return over the period of a few consecutive years.

Luddam’s Ford Park Dam

One November in the early 80s, while canoeing the lower Indian Head, I watched as dozens of cohos spawned in the marsh, making their redds (nests) on a patch of gravel. I didn’t know it then, but the dam just upstream doomed any offspring of those fish. Just as the dam blocked the cohos so that they could be captured and stripped of their milt and eggs, the high summer temperature of the water flowing over the Luddam’s Ford Park dam made sure that any coho salmon fry that hatched from the redds – from natural reproduction – would not survive the summer.

For Marine Fisheries, the ability to block the upstream passage of the salmon, and high summer temperatures in the impounded river above the dam, were among the conditions that made the Indian Head River a desirable location for the introduction of Pacific salmon. The Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries needed to be able to abruptly end the run if the introduced cohos began to compete with, or otherwise damage native fish.

While the North River’s coho salmon fishery ended for reasons that are still not fully understood, the New Hampshire coho salmon program apparently did end deliberately. The federal government, and the state of Maine, had long been struggling to restore our native Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) to their rivers. These rivers included the Merrimack River, along with a number of rivers along the Maine coast, many of them smaller, and potentially within the range of the coho salmon being introduced to the streams entering New Hampshire’s Great Bay. It was feared that the cohos might begin to successfully reproduce in Maine rivers, a situation that would make protecting and restoring the last remaining native Atlantic salmon all the more difficult. As a New Hampshire fisheries biologist stated, the coho salmon came to be viewed as an invasive species and that introducing them was potentially causing more harm to our already endangered native salmon.