The following story was unearthed recently. It tells the tale of the Brig Polly, a 131 ton ship constructed in Pembroke in 1791. She was probably built by shipbuilders Alden Briggs, Calvin Turner and Icabod Thomas, Jr. Her home port was Boston.

The following story was unearthed recently. It tells the tale of the Brig Polly, a 131 ton ship constructed in Pembroke in 1791. She was probably built by shipbuilders Alden Briggs, Calvin Turner and Icabod Thomas, Jr. Her home port was Boston.

Lost Ships and Lonely Seas by Ralph D. Paine 1920

A hundred years ago every bay and inlet of the New England coast was building ships which fared bravely forth to the West Indies, to the roadsteads of Europe, to the mysterious havens of the Far East. They sailed in peril of pirate and privateer and fought these rascals as sturdily as they battled with wicked weather. Coasts were unlighted, the seas uncharted, and navigation was mostly by guesswork, but these seamen were the flower of an American merchant marine whose deeds are heroic in the nation’s story. Great hearts in little ships, they dared and suffered with simple, uncomplaining fortitude. Shipwreck was an incident, and to be adrift in lonely seas or cast upon a barbarous shore was sadly commonplace. They lived the stuff that made fiction after they were gone.

Picture the brig Polly as she steered down Boston harbor in December 1811, bound out to Santa Cruz with lumber and salted provisions. She was only a hundred- and thirty-tons burden and perhaps eighty feet long. Rather clumsy to look at and roughly built was the Polly as compared with the larger ships that brought home the China tea and silks to the warehouses of Salem. Such a vessel was a community venture. The blacksmith, the rigger, and the caulker took their pay in shares, or “pieces.” They became part owners and did likewise the merchant who supplied stores and material; and when the brig was afloat, the master, the mate, and even the seamen were allowed cargo space for commodities that they might buy and sell to their own advantage. A voyage directly concerned a whole neighborhood.

Every coastwise village had a row of keel-blocks sloping to the tide. In winter weather too rough for fishing, when the farms lay idle, the Yankee Jack of all trades plied his axe and adz to shape the timbers and peg together such a little vessel as the Polly.

Nowadays, such a little craft as the Polly would be rigged as a schooner. The brig is obsolete, along with the quaint array of scows, ketches, pinks, brigantines, and sloops which once filled the harbors and hove their hempen cables short to the clank of windlass or capstan-pawl, while the brisk seamen sang a chantey to help the work along. The Polly had yards on both masts, and it was a bitter task to lie out in a gale of wind and reef the unwieldy single topsails.

On this tragic voyage she carried a small crew, Captain W. L. Cazneau, a mate, four sailors and a cook who was a native Indian. Two passengers were on board, “Mr. J. S. Hunt and servant girl 9 years old.

Four days out from Boston, on December 15, the Polly had cleared the perilous sands of Cape Cod and the hidden shoals of the Georges. Mariners were profoundly grateful when they had safely worked offshore in the wintertime and were past Cape Cod, which bore a very evil repute in those days of square-rigged vessels.

The Brig Polly said her course to the southward and sailed into the safer, milder waters of the Gulf stream. The skipper’s load of anxiety was lightened. He had not been sighted and molested by the British men-of-war that cruised off Boston and New York to hold up Yankee merchantmen and impress stout seamen.

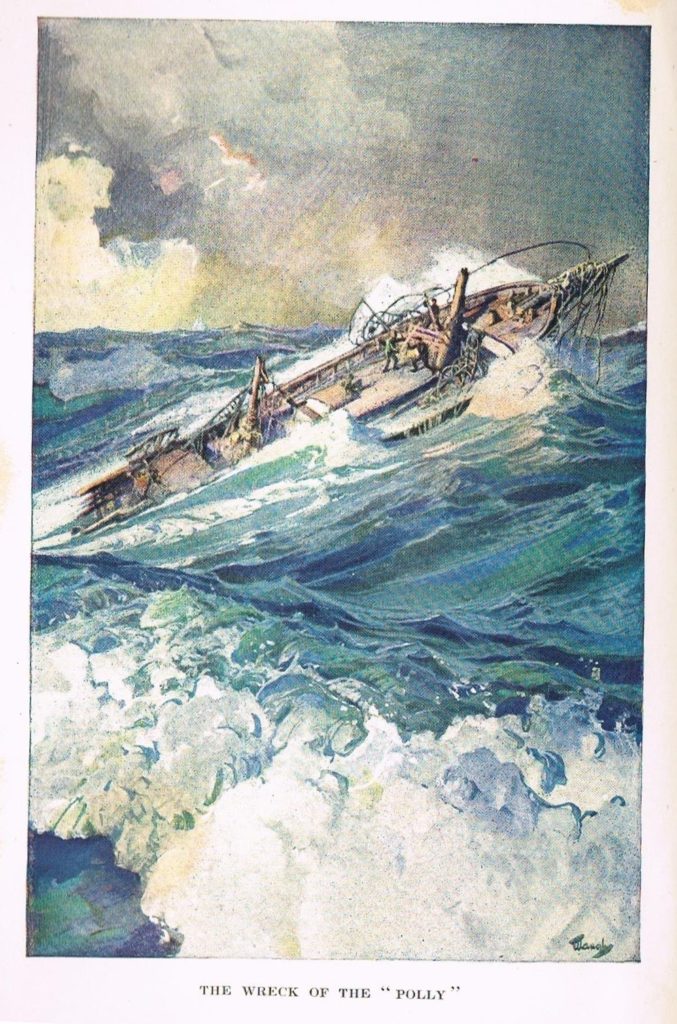

Seamanship was helpless to ward off the attack of the storm that left the brig a sodden hulk. Courageously her crew shortened sail and made all secure when the sea and sky presaged a change of weather. These were no green hands, but men seasoned by the continual hazards of their calling. The wild gale smote them in the darkness of night. They tried to heave the vessel to, but she was tattered and wrenched without mercy. Stout canvas was whirled away in fragments. The seams of the hull opened as she labored, and six feet of water flooded the hold. Leaking like a sieve, the Polly would never see port again.

Worse was to befall her. At midnight she was capsized, or thrown on her beam-ends, as the sailor’s lingo has it. She lay on her side while the clamorous seas washed clean over her. The skipper, the mate, the four seamen and the cook somehow clung to the rigging and grimly refused to be drowned. They managed to find an ax and grope their way to the shrouds in the faint hope that the brig might right if the masts went over the side. They hacked away until the foremast and mainmast fell with a crash and the wreck rolled level.

At last the stormy daylight broke. The mariners had survived and looked to find their two passengers. Mr. Hunt was gone, but his servant girl lived no more than a few hours. The Polly could not sink, but she drifted as a mere bundle of boards with the ocean winds and currents while seven men tenaciously fought off death and prayed for rescue.

The gale blew itself out, the sea rolled blue and gentle, and the wreck moved out into the Atlantic, having veered beyond the eastern edge of the Gulf Stream. There was raw salt pork and beef to eat, nothing else. A keg of water found to contain thirty gallons. For twelve days they chewed on this salty raw stuff and then the Indian cook, Moho by name, succeeded in kindling a fire by rubbing two sticks together in some abstruse manner handed down by his ancestors.

The tiny galley was lashed to ringbolts in the deck and had not been washed into the sea when the brig was swept clean. So now they patched it up and got a blaze going in the brick oven. The meat could be boiled, and they ate it without stint. The cask of water was made to last eighteen days by serving out a quart a day to each man. Occasional rain saved them for a little longer from perishing of thirst. At the end of forty days they came to the last morsel of salt meat. The Polly was following an aimless course to the eastward, drifting slowly under the influence of the ocean winds and currents. These gave her also a southerly slant, so that she was caught by the vast movement of water known as the Gulf Stream Drift towards the coast of Africa.

At the end of fifty days of this hardship, Mr. Paddock languished and died, seven days later a young seaman named Howe likewise died delirious and in dreadful distress. Fleeting thunderstorms had come to save the others and they caught a large shark by means of running a bowline slipped over his tail while he nosed about the weedy hull. This they cut up and doled out for many days. It was certain however that unless they could obtain water they could not survive for long.

Captain Cazneau seems to have been a sailor of extraordinary resource and resolution. His was the unbreakable will to live and to endure which kept the vital spark flickering in his shipmates. Whenever there was strength enough among them, they groped in the water in the hold and cabin in desperate hope of finding something to serve their needs. In this manner they salvaged an iron teakettle, a barrel from one of the captain’s flint-lock pistols, a whittled wooden collar, cloth and pitch scraped from the deck-beams to form a crude apparatus for distilling seawater.

Imagine those three surviving seamen watching the skipper while he methodically tinkered and puttered. It was absolutely their one and final chance of salvation. Their lips were black and cracked and swollen, their tongues lolled, and they could no more than wheeze when they tried to talk. They kept the fire going night and day for their daily allowance of water limited to about a pint a day.

Yet, the faithful cook died in March after three months adrift followed by the death of seaman Johnson in April. Three men were left aboard the Polly: the captain and two sailors.

The brig drifted to that fabled area of the Atlantic known as the doldrums of the Sargasso Sea between the Azores and the Antilles, the dread of sailing ships. Carpets of weed engulfed the brig, unable to push herself through these acres of leathery kelp the crew discovered the stagnant weed swarmed with fish, crabs and mollusks. They hauled masses of weed over their broken bulwarks and picked off crabs by the hundreds, fished with “hooks” fashioned from nails and even dried them in the hot sun or salted some from the sea-salt collected in the bottom of their still.

The Polly had been adrift for four months, Captain Cazneau’s account omitted the death of another sailor after April. A shelter was made weatherproof with shingles discovered in the hold and with only two survivors left, there was enough fresh water to survive. The mysterious impulse of currents plucked at the keel of the Polly and cleared her out into the Atlantic again.

The brig drifted toward an ocean frequented by Yankee ships none of them sighted the speck of a derelict floating almost level with the sea with no visible spars or masts. Captain Cazneau and his companion saw sails glimmer against the skyline during the last thousand miles of drift, but they vanished like bits of cloud and none passed near enough to bring salvation.

June found the Polly approaching the Canary Islands, a journey of some two thousand miles. The wreck would soon have stranded on the coast of Africa. It was on the twentieth of June that the skipper and his companion – two hairy, ragged apparitions – saw three ships which appeared to be heading in their direction. Not one ship, but three, came bowling down to hail the derelict. The captain of the nearest one shouted a hail through his brass trumpet, but the skipper of the Polly had no voice to answer back. He sat weeping upon the hatch. Although not given to emotion, he would have told you that it had been a hard voyage. A few minutes later, Captain Cazneau and Samuel Badger, able seaman, were alongside the good ship Fame of Hull, Captain Featherstone and lusty arms pulled them up the ladder. It was six months to a day since the Polly had been thrown on her beam-ends and dismasted.

The skippers gave the survivors of the Polly a welcome and marveled at the yarn they spun. The Fame was homeward bound from Rio Janeiro. They were transferred to the brig Dromio and arrived in the United States in safety.

A wise old mariner once said, “Ships are all right. It is the men in them.” This was supremely true of the little brig that endured and suffered so much, and among the humble heroes of blue water by no means the least worthy to be remembered are Captain Cazneau and Samuel Badger, able seaman, and Moho, the Indian cook.